Ballock or Bollock daggers

Ballock or Bollock daggersBollock daggers and kidney daggers: an ethnography of classification work in museums.

Terry Hemmings, Dave Randall, Dave Francis and Liz Marr

.Abstract

This paper reports on some aspects of an ethnographic study of museum work. The research took place in two locations in the UK and the emphasis here is on how we might conceive of classification work as essentially co-operative and contingent.

Terry Hemmings.

School of Computer Science and Information Technology.

University of Nottingham.

Nottingham. UK.

terry.hemmings@nottingham.ac.uk

Dave Francis, Liz Marr and Dave Randall.

Department of Sociology.

Manchester Metropolitan University.

Manchester. UK.

Background.

This article is based on an unpublished paper that reported on an ethnography carried out during 1996/7. That draft aimed at addressing themes relevant to the CSCW community. Some four years later, those themes and substantive issues raised seem just as pertinent now as they were. Some minor revisions have been made to the text and a number of images have been included in this on-line version.

Although we embarked on our study of the ‘museum’ with one eye on some fairly standard sociological interests, including the cultural work of museum curators, the other was very much on the CSCW research agenda. After all, museums are organizations like any other, involve a great deal of ‘work in common’, are saturated with both tacit and explicit knowledge that may be shared by their professional members, but is invisible to outsiders, and are experiencing the same economic pressures that have affected organizations more overtly in the commercial arena. It seemed, therefore, that the development of multi- user or 'co-operative' technologies might impact as much on their work as elsewhere. In many respects, in Europe at least, public service institutions have only recently begun to recognise the potential value of Information and Communication technologies as devices for cost effective and enhanced delivery of their services. Indeed, before we even began the study, the self confessed naivety of practitioners in this arena was marked. This manifested itself in a general anxiety to join a perceived revolution, for instance by ‘getting on the Net ... we’ve just had our Home Page done for us ...’ as somehow constituting a solution to a set of developing organizational problems. Of course the more jaundiced eye recognises that new technology provides no guarantee of success. CSCW ‘case histories’ provide many evaluations of 'failed' or ‘underused’ systems, including for brief mention the London Ambulance Service debacle, the abortive Taurus system for the stock exchange, underused equipment in domains such as Air Traffic Control (Shapiro et al, 1991), and Building Societies (Randall and Hughes, 1994). It was clear from the outset that museum managers and curators recognise the relevance of computer technology to their work, are anxious to find applications that might support it, and are frustrated when they discover that existing applications are of a very generic kind. They were, however, self confessedly naive concerning the possible functionalities available to them. This naivety constituted something of a research problem, in the absence of any coherent view of what the technology might be ‘for’. Staff we talked to, whilst undoubtedly enthusiastic for new technologies in public information domains were not only entirely unfamiliar with concepts like CSCW, but apparently with the basic notion of ‘requirements’ let alone any sense of their complexity. (Jirotka and Goguen, 1994) The ethnography began ‘innocently’ (Hughes et al, 1991), that is, but to a large extent has remained so. The study, then, has covered a range of issues, including the work of curators and archivists, designers, marketing personnel, ‘educators’, management, intra- and inter- museum relations, and so on. Some, but not all, of the work we observed was germane to the use of technology. Where technology was seen as relevant, it was in terms of some very general considerations of ‘potential’ in areas where our colleagues at the two museums were concerned. The problems and the promises, for brief mention, were held variously to include:

Even so, and as CSCW practitioners recognise, where in principle new systems offer avenues for solving various long standing problems museums and similar institutions may have, the question of how to address them in practice remains obdurate. How to ensure promises are realised is still a vibrant issue. Our research was in keeping with other sociological studies in CSCW, which have advanced ethnography as a candidate method for ‘informing’ the design of technology (see for example Pycock and Bowers, 1996; Randall et al, 1995), and which are for the most part predicated on the view that the effective use of technology relies on the degree to which it can be thoroughly embedded in the ordinary and practical purposes of people who are working with it. Our argument here is that the potential value of electronic systems for museum users relies on precisely the same understanding of the work done by museum staff.

We concentrate in this paper on classification work and how it is done by curators and archivists, largely because it relates very much to problems of recording and using database information, because the use of database applications is more advanced in museums than any other kind of application, and because curatorial practices enable us to make classification visible as work and at that co-operative work, rather than as the deployment of pre-existing categories in stable hierarchies. What we try to do below is present an account of the kinds of relevant practice that need to be understood as classification work before the process of identifying what is 'appropriate' computer support can be undertaken.

The Ethnography.

Our analysis is based on an ongoing two year ethnographic study of the work of museum staff and visitors in two locations in the North of England; the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester (MSIM) and the National Railway Museum in York (NRM), concerned in part with what might be called 'scoping' the problem of information use at the museums in question. That is, we have been mainly concerned with an attempt to understand what kind of work is undertaken, and by whom, and how this work might prove to be relevant to information needs. Our study continues and we have currently completed about a year of observation. Our reasons for focusing on the museums in question had to do with local accessibility and the existence of contacts who could facilitate entry.

We began to recognise early on that some features of museum work, for us at least, had been previously unconsidered (but see Star and Griesemer, 1989). Firstly, museums have a history. By way of example, the origination of the Manchester museum was as a small scale, almost personal enterprise prompted by the interests of an individual in the history of engineering. The museum at that time, therefore was seen as ‘his personal project’, or, ‘run like a fiefdom.’ The fundamental function of the museum then was perceived as educational, quite specifically as an ‘aid to schooling’. It grew when offered a railway goods yard and all the artefacts it contained. The museum then became situated historically at the location of the world's first railway station, and this informed the formation of a set of embedded assumptions about 'what was important'. The original source of funding was the local council, and this in turn influenced policy- a policy that was essentially parochial and very much to do with what was perceived as ‘locally relevant’- especially since the 'Manchester' connection determined things like funding support for acquisition. In a nutshell, enthusiastic amateurs, for whom the evolution of policy was a more a question of deciding what it was that they were enthusiastic about at the time, ran the museum. Policy was, of course, progressive, and management and curatorship increasingly professional. Nevertheless, this brief history indicates the way in which we want to understand policy concerning relevant acquisitions and display decisions- as being arrived at in the ‘doing’ of decisions concerning 'what do we want' and 'what don't we want?'

Secondly, where we might have assumed that curatorial functions were akin to detective work, happening on clues to the whereabouts of rare and valuable items, and tracking them down, the reality here was startlingly different. The most surprising aspect, for us, was the fact that both museums are confronted with an almost endless supply of artefacts and materials. Their problem is less to do with how to find exhibits, but with how to decide what to keep and what to reject, and the former greatly exceeds the latter. That is, the museums are essentially engaged in sorting work. This is manifested above all in ‘accessioning’ and ‘de-accessioning’, or deciding what should constitute the ‘collection’. To the extent that both museums acquisition policy suffered the affects of ‘embarrassement de richesse’ and so the availability of storage space has a significant impact on what can be kept and what cannot.

Thirdly, we quickly became aware of a tension between on the one hand an intellectual climate in museum life which problematises ‘meaning’ and on the other a ‘rationalising’ tendency which seeks to stabilise it in computer systems. Writers on museums have identified the former as a fundamental aspect of the changing nature of museum work. The changing status of the museum, and accounts of its 'proper' purpose, have been problematised by post-structuralist/ post-modern views of the status of knowledge, whereby the Enlightenment conception of history as a rhetoric of progress has been increasingly challenged. These arguments, whatever one makes of them, have included the decline of the meta-narrative (Lyotard, 1984), the post-modern condition as simulacrum or 'spectacle' (Baudrillard, 1983), and the recognition of the contingent and historically specific locus of discourse, not to mention aspects of 'power/knowledge' (Foucault, 1980). Along with the pull of the commercial nexus, post-modern discourses have substantially affected the sense of the curatorial function of the museum. (Kopytoff, 1986) In other words, curators are now arguably required to be responsive to competing views concerning the meaning and organisation of knowledge. Thus, it was possible to argue that the 19th century conception of the museum was to achieve 'by the ordered display of selected artefacts a total representation of human reality and history' (Donato, 1979 quoted by Bennett, 1995: 126), wherein 'as educative institutions, museums function largely as the repositories of the already known.' (ibid:147). As Bennett points out, "few museums draw attention to the assumptions which have informed their choice of what to preserve or the principles which govern the organisation of their exhibits .... yet, as it has been my purpose to argue, this question of how is a critical one, sometimes bearing more consequentially on the visitor's experience than the actual objects displayed." Such concerns open up a difficult analytic terrain to do with how one might organise and classify artefacts and texts.

The countervailing tendency, the force of which is a move towards a standardised ‘sense of order’ can be seen in a progressive move towards systems which might support curatorial and management work. They can be understood, then as what Star and Griesemer see as a form of ‘boundary object’ devised as ‘methods of common communication across dispersed work groups’ (op cit, p411) Certainly, there is a view that much is to be gained in terms of collection management by the use of database applications in which standard descriptions can be inscribed and accessed. This would allow much wider access, in that data about collections would be available to many more people, and arguably would reduce dependency on individual curatorial expertise. We are broadly neutral on whether these objectives are attainable or desirable, but are interested in the practical problems associated with arriving at descriptions that would fit easily with the right database application, such that ‘doing the work’ is enhanced by effective computer support, rather than obstructed. This issue has an abiding relevance as museums work less and less in isolation, and more in collaboration. The developing national and international relations between museums in similar fields creates an apparent push for some kind of control over vocabulary, such that comparison work can be made feasible. In other words, there seems to be a general acceptance of the need to standardise usage, if it can be done. The difficulty of achieving this goal may, however, be estimated from the fact that according to one curator, ‘there are 600 different Thesauri in existence in Europe alone’.

The desire to create a more standardised system led to the creation of a system which was, at the time, being trialled and used by a consortium of British museums, and which is called Multi-Mimsy. There are currently 8 or 9 institutional members of the museum group called LASSI, who are committed to using Multi-Mimsy to provide a national database system, collating information across all members, information which will incorporate functions such as collection management, access statistics, administration, and so on. One of our sites, the National Railway Museum is proposing to use it. However, both the logic of the system and LASSI policy dictate that local practices and local languages will not supported (Although the database does have a facility for locally nominated categories, these can only be applied in restricted fields). There is in operation, if you will, a kind of categoric imposition. This means that any descriptions to be placed on the system must use either use words already in the Multi-Mimsy thesaurus or must be proposed as a candidate for the thesaurus. In other words, the very terms that can be used to describe objects have become a policy issue decided at a level beyond that of the individual museum curator. In the case of Multi-Mimsy, the thesaurus in question is based on an Art and Architecture vocabulary.

As we have stressed, research into database applications that might support museum work is in its infancy, and we do not want to be unnecessarily critical of first generation systems. Nevertheless, even a cursory look at the curator’s ‘problem’ reveals a tension which is not easily resolved, a tension between a historically evolved ‘methods standardization’ and developing ‘boundary objects’ such as the database (again, using Star and Griesemer’s terms). The force of Multi-Mimsy, on the back of the recognised need to standardise, is to ‘clean-up’ the number of local terms used to identify an object an in turn reduce the number of categories deployed. The curator, however, is an expert in his or her field precisely because they are able to deploy categories that are ‘relevant’. Thus, one curator involved in discussions concerning the system put it like this:

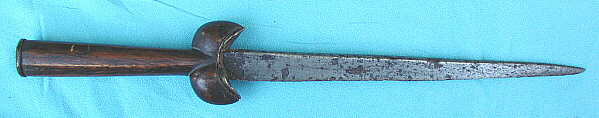

"My speciality is early arms. Essentially, I’m interested in daggers, in the different kinds of daggers and swords and what they were used for and how they and the different design. They are not just daggers. You have to bear in mind that the system allows you to enter a record as a ‘sword’- that’s it, sword- when I want to record the difference between ballock daggers and kidney daggers. These things had different usages, different ceremonial functions and were carried by different people. Ask yourself, when does a sword become a dagger?"

Ballock or Bollock daggers

Ballock or Bollock daggers

The term ballock or bollock is course slang for testicles and is a derivation of the Old English bealluc (ball). The ballock knife is distinguished by two rounded prominences or ballocks that serve as a guard. This ancestral dirk has variously been called a dague, a couilettes, a phallic dagger. During the more modest Victorian era, it was referred to as a "kidney" dagger. Other written records refer to dirks, dorks, and durches. All names are presumed to be the local vernacular for the ubiquitous ballock knife.

Kidney Dagger

Kidney Dagger

Classification work.

Understanding museum work, then, means seeing it as having a historical character, as the sedimentation of things that have happened, chronicles of events and significant developments, and of the roles and consequences of artefacts. It is constituted in short as the ‘ordering’ of history. In the sociology of museums this has been much remarked upon, as outlined above, generally in terms of the way the order of things, to use Foucault’s formulation is an ideological or discursive construct (see Bennett, ibid, Macdonald and Fyfe, 1996) and how these are spaces which have been opened up in the ‘post-modern’ era for contestation, for instance by feminist scholars (see Porter, 1996). Competing views of history, then, inform the work of curators to a greater degree than ever before, along with the recognition that their interpretive work is at best ‘partial’ and incomplete. Regardless of this rhetoric, however, our interest here is the way in which the coherence of classificatory schema is arrived at and maintained, for in the work one of the most striking features is the way in which agreements at the level of classification need to be reached before there can be any disagreements about significance. Even so, classification is above all the work of making history coherent, of arriving at definitions that are suggestive of the ways thing relate. Relevancy decisions are made precisely with an eye to the way things ‘fit’- and using those definitions as ‘working hypotheses’ or resources for further coherency work. That is, classification is used to produce order, and is produced in turn by it. The point here is that these categorisation devices are the rationale by which curators arrive at mutual understandings of what it is that they are doing. It is, in short, accounting work. Such a description may make it appear that inscribing terms and usages in databases will be no more complex than for any other set of terms, and so it would be if the coherence we refer to led to a single usable hierarchy of terms. That is, if usage could be made ‘planful’ such that all new objects and texts could be made to fit an existing thesaurus unproblematically. The problem is precisely that it cannot easily been done.

Our interest in the way in which objects are specified as being 'of a certain kind' relies on uncovering the knowledge and experience which informs the practical, day-to-day, work of curators and others. For example, one way in which this work is made visible is when considering acquisitions and their cataloguing. Unsurprisingly, museums need to do this. Institutions of this kind after all would find it difficult to operate without recorded knowledge of the artefacts they own or control. Nevertheless, it is more than simply making a list. The inscriptions that are generated, be it in the catalogues, the cards accompanying displays, or the fields in databases they use, indicate not just the name of the object, but its status. That is, the act of examining and inscribing the object’s status is an attribution of ‘value’. They are examples of what Berger and Luckmann term ‘typifications’ (Berger and Luckmann, ), but typified according to relevancy criteria determined by expert judgement. Deciding ‘what kind of object it is’, then, is a matter of providing a brief description that incorporates judgements concerning issues such as ‘provenance’, ‘uniqueness’, and ‘relevance to the collection’.

In both the museums we are examining, objects arrive and leave in a more or less continuous stream as candidates for inclusion. To reiterate the point, artefacts regularly arrive at the museum unaccompanied by any form of ‘authority’. They are merely candidates for inclusion, and their inclusion confers an authority upon them. In other words, an authenticity is granted them by virtue of inclusion, and they stand as ‘authentic’ to the visitor as a result procedures for 'theming' exhibits within the museum, for deciding what to display and where, for cataloguing the collection and so on, are reflexively linked to classification schema. Classification, however, is an increasingly problematic area. In this respect, the developing interest in the relationship between image and text (Burgin, 1986a, 1986b) is relevant. Whilst not wishing to engage with the explicitly political rendering of meaning that Burgin and others are concerned with, it is clear that serious issues concerning the classification and 'meaning' of artefacts are raised. Providing 'coherent' and 'relevant' themes is a matter of organising artefacts and text, not merely representing them. The limitations of physical spaces mean that, often, only highly constrained choices are available. An initial example concerns a large Goss printing machine currently in the possession of the Manchester museum. We were present at discussions concerning whether this machine should be de-accessioned, which in effect means finding another institution that might be interested in it, or otherwise scrapping it. What is interesting here is not the machinery, but the rationale that was brought to the discussion, which included a discussion of ‘provenance’, a term covering the history of the machine, the site it came from, the local relevance of both the site and the machine itself, the importance of the printing industry to the local area, where it was made and so on. Points at issue included that the machine itself was not made in Manchester, but was a major technological development in the development of the printing trade in Manchester, that chronicling the history of printing necessitated the ownership of key machines, but that printing was ‘no longer that important’ locally. The point here is not that these factors are the most important in determining the fact of an artefact, but that they were the most important governing the fate of this artefact. That is, an account is provided which has to do with changing assumptions about its value. This whole discussion takes place against another background, that of available space. The fact of the matter is that printing machines are very substantial, and retaining it weighs against the acquisition of other things. In a nutshell, objects have careers. Hence:

Needless to say, not all artefacts are large objects. Many are text based, and as it were, come bundled. The result is that they have to be searched, sorted and identified in order to establish what their value, if any, is. By examining one such example of artefacts arriving at MSI, which consisted of two archives from large electronics companies based locally, we can identify some of these themes. In the first instance, a large collection of text-based materials was accepted from a company which had been based in Oldham, a town near to, but not part of, Manchester. Subsequently, a bigger archive, which included photographs and detailed historical records, was offered from GEC, a company based in Trafford Park, a region of Manchester.

Of course, such materials do not arrive prepared and ordered for museum use. The curators, in their own words, must ‘do a job on it’. Watching them examine the material, it is clear that the physical nature of the artefacts in question provides a variety of accessing routines. Some of the material is flat, some of it consists of photographs of buildings, machinery and people, some of it is large format paper, and thus can be unfolded, as with blueprints, etc. Some of it is sequentially ordered to reflect a development. The practiced eye of the curator can see how this material could in principle be organised- its potential as a display item or as a 'fileable' resource. As the material is accessioned, knowledge is applied to it-

'oh, this would do for ... look, photos of Trafford Park ... you can see the development ...'

‘GEC is a big international company, but its got a local history. I mean, GEC is Trafford Park, and Trafford Park was once the world’s biggest industrial centre ...’

‘the [other] archive is just not so interesting ...’

As they are unpacked, the materials are ‘seen’ as what they might be. Drawing on the kinds of relevancy we mention above, the archivist is able to tease out the social, political and economic relevance of the material, and thus how it might be ordered for the visitor or the professional interrogator of such material, in and through the sorting that is going on. The 'interpretation work' that is taking place is ‘doing’ work. It is the physical work of separating material into piles, noting that some parts of it have a particular relevance, some could be incorporated into other displays, some have ‘exhibition’ potential, and so on. Notably, the criteria being applied centre on the local relevance of the material, as in ‘GEC is a big international company, but it’s got a local history’, and on the significance of the material, as with, ‘oh look, photos ... you can see the development ...’ and ‘Trafford Park was once the world’s biggest industrial centre ...’. In other words, the sorting and classifying of the material is done with an eye to the story that can be told, and a story that is in keeping with known-in-common criteria. Curators evidently ‘know what they mean’ when they use terms like, ‘is an example of’, ‘is typical of’, ‘is a rare example of’, ‘is of the school of’, is ‘the first’ or ‘last example of’ or is ‘a common type of’ and such terminologies are reflexively deployed against, in this instance, background assumptions concerning the museum’s interest in ‘local’ matters and in ‘industry’, as well as ‘what we can do with it’. All of these usages, despite their sometimes contradictory status, might at some time be used as justifications for retaining or acquiring a particular piece. The objects present themselves as candidates for inclusion and are sorted on the basis of what ‘is interesting’ about them. What is interesting is determined not only by assumptions about the object itself, but by the determination of the curator’s practiced eye deciding on its ‘place’ in the collection, a place which is determined by the status of all the other objects in the collection and the curator’s knowledge of their relationships. Here, the work has much in common with Heath and Luff’s observation (1996) that, "the [records] must inevitably embody a powerful and generic set of practices which inform both the writing of the record and their reading ..." for much like the medical records in question, museum catalogues include the known in common, mutually understood usages we refer to above.

For MSI in particular, the judgements arrived at are dependent on criteria such as whether it has local relevance, whether it has significance for the subject area of the museum, whether it is unique, and the object's provenance. These matters, it turns out, are important not only for accessioning but also for de-accessioning. Museums of this kind have any endlessly changing set of potential exhibits and frequently wish to move objects elsewhere, or simply dump them. The point here is that the Accessions catalogue constitutes a brief record of the rationale for accepting objects or disposing of them. Not least, it seemed the entering of descriptions in the catalogue gave a status to the object, a status that is arrived at by discussion and subsequent agreement among participants. In other words, the work of cataloguing is the work of defining objects as being of a 'of value' for specified reasons. What is being recorded, so to speak, are curatorial agreements concerning the 'value' of potential exhibits. A more complete picture of the things that decide 'object value' in this work, we think, would tell us much about appropriate categories for database organisation.

On the back of this example, we can make a number of points about representing the status of objects, including that it is not a matter of imposing a rigid classification scheme, but of using existing classifications for deciding 'what you can do with it.':

As any practitioner will know, museum work is complex. Classifying work does not go on in any single place, or stage of an object’s career, and is not solely the responsibility of the curator. Museums employ staff with various responsibilities, which typically include, for instance, professional designers employed for exhibition purposes, educational work of an organised kind, as well as marketing, and administration functions. In addition, professional staff frequently rely on networks of enthusiastic amateurs for aspects of their work, as we shall see. On many occasions, these roles become rather fluid, and it is difficult in practice to entirely distinguish between what designers and educators do, and what curators do. There is no space here to detail all aspects of the work, so we content ourselves with referring briefly to two others. We do so because in different ways they demonstrate the contingency of classification, according to the purposes at hand. Analysis of artefacts and their allocation to suitable categories takes place then when exhibitions are put together and when responding to enquiries. The 'in house' work of preparing for more permanent exhibition is considerable. Here, the work is that of selecting relevant exhibits, structuring them in an orderly and coherent way according to the 'story' they are trying to tell, and providing a narrative text. Again, the work of producing the story is invisible to the outsider and is produced out of discussion and agreement concerning the status of objects that an exhibition might contain, and how they relate to each other. However, these relations are contingent on the exhibition in question. It is, one might say, deemed 'like this' for 'this purpose' although it might quite well be described in other ways for other purposes. Further, it is not as if the story to be told comes fully formed. The production of the exhibition is as much the production of a story as it is the production of an organised set of artefacts, and they inform each other. The objects, the accompanying text, and the positioning of the object vis a vis others together tell the desired story.

Other relevant classification work can be seen in response to enquiries, typically by telephone or in person. Indeed, in the museums in question, this fact is recognised and institutionalised through rota systems for dealing with them. Although many of these enquiries were of a routine nature, some were not. There is, for instance, the occasional request from the media to provide information of a more in-depth kind than one would expect from a typical member of the public. Our point here is that answering enquiries can be far more than merely giving an answer to a self- evident question. In such situations, responding to an enquiry can be a process of identifying exactly what it is the enquiry is about, and can involve identifying, finding, and preparing, the 'local expert' to answer the enquiry in question. The social distribution of knowledge and expertise is a common feature of organisational life, and we have seen elsewhere (for instance in studies we have been involved in the financial sector) that asking and answering questions, whether it be from customers or colleagues, is a frequent and surprisingly complex activity. The point here is that 'answering enquiries' sometimes involves making sense of 'what kind of enquiry it is', a task human beings are well suited to. 'Understanding the question' and 'Finding the person who knows the answer' relies on 'what the respondent knows' as part of his or her professional expertise. Embedding this expertise into systems intended to answer the questions visitors or staff may have is anything but a simple exercise. It relates directly to the problem of database interrogation and certainly involves more than the 'Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)' framework commonly found on the Internet. The point here is that classification schema embedded in computer databases do not necessarily pay due regard to the fact that relevant classification is contingent upon the task in hand.

Our argument, then, is that classification work involves the production of a ‘sense of order’ out of the myriad artefacts and texts available. Despite the recognition that historical interpretation is a contingent matter, there is not, and has not been to our knowledge, any serious suggestion that museums could get by without managing objects into ‘orderly’ collections. The ‘sense of order’, in other words must precede any subsequent disagreements about its partiality, and we need to understand more fully how it is arrived at, if we are to successfully evaluate the possibility of developing standardised usages. The following example that came to our attention took place over a period of time at the NRM, and involved the senior curator in the engineering department of the museum and a network of enthusiasts as they evolved a suitable classification scheme for a particular kind of railway truck. The background to this is that for the visitor to the NRM, steam trains are redolent of many things. They evoke, for many, a ‘romantic’ past. Steam engines, it seems are 'of interest', and the museum can trade on a number of assumptions about the public’s enthusiasm for their history, including the apparent attraction of ‘steam’, science and engineering issues, political and cultural background, etc. Not least, they have a large and impressive physical presence. Notably, however, this enthusiasm for the engine on the part of the public is not accompanied by any enthusiasm for the rolling stock. ‘Wagons’, as aficionados term them, have other characteristics, which seem to make them less interesting to the public, including that they are exceedingly common, they are not easily distinguished one from another by the unpracticed eye, they are not ‘nice to look at’, and so on. Nevertheless, for the railway expert there is a considerable interest. A number of historical developments meant that certain wagons were manufactured to do certain jobs in certain locations. For instance, wagons specifically designed to transport clay from Cornwall to centres of paper finishing in the North of England, were built as the rail network developed to allow large scale transportation. This, it seems, involved a number of problems, including the fact that the existence of private regional companies meant different sized gauges had to be contended with. Such matters, however obscure to the rest of us, are interesting to the curator. In terms of classification, an operational scheme existed for indexing these wagons according to what is known as a TOPS number. Such a scheme, however, is of no value to the curator since the index is operationally defined, meaning that it distinguishes only by criteria such as axle weight and payload. Operationally, TOPS allowed one to determine whether one set of wagons could be connected to another, and what engine could tow it. Marshalling was dependent on this scheme. The TOPS number is of no value for curatorial purposes, precisely because the historical significance of the object is not equivalent to its operational significance. The object has changed. At the NRM, the group in question had determined that the historical part played by the wagon in the development of the railway had been somewhat under-researched, had if you will something of a ‘cinderella’ status, and set out to catalogue and classify all existing wagons of a particular kind. The classification issues here turned out to be markedly different from those implicit in their operational value, and were evolved as part and parcel of the work of recording their existence. In brief, it was decided that the network of enthusiasts would ‘spot’ these wagons in much the same way that trains are ‘spotted’, but that in so doing they would record certain relevant details, most notably where the wagon was to be located, the condition it was in, and so on. Each agreed that when embarking on this exercise they would photograph the artefact in question, and record the relevant details in notebooks. This candidate classification scheme again had to do with ‘provenance’, carried and organised in and through a small group’s discussions of what needs to be recorded so that the recording could be done at all. It was evolved through the 'taken for granted' background knowledge about typical classification devices that enthusiasts and curators share. The point is that, as with all classifications, the terms used need to be consistent if they are to be recorded for comparison work, so categories such as ‘rotting’, ‘wheels on or off’, ‘coal’, ‘clay’, ‘manufacturer’, etc. were agreed on. That is, and in the first instance, some ‘broad brush’ classification enabled the work of ‘collecting’ data to take place. We might refer to these as candidate classifications, in that they will ‘do’ for the purposes in hand. They are socially organised agreements which have not yet reached the status of methodological standardisation in any but a very restricted sense, for the ‘method’ is not yet open to inspection by others with an interest in the same objects.

As information began to amass, the problem became one of organising it into an orderly record. The brief details were, therefore, brought back and put into an A4 ring binder. Entries were placed in the binder chronologically in order of date ‘spotted’. Using this binder all the time, and getting used to 'where things are' in the binder allowed the group to do comparison work, such that using the record as a pre-classified resource allows members of the group to compare discoveries with existing finds, and thereby to generate their own knowledge of the ‘state of play’. As their endeavours grew, so it became evident that a more effective recording system was required, largely because the work itself had produced a greater sense of its importance. That is, in the words of the senior curator, "its important work ... we can’t keep all these wagons, and many of them are deteriorating ... its the only record we have of a part of Britain’s industrial and transport history." It was thus decided that the information be transferred to an electronic database, purchased ‘off the shelf’ for its customisability (called ACCESS). A set of criteria were worked out, which were: TOPS; geographical location; the owner; date of manufacturer and the who manufacturer was; a photograph. On top of this, a scale of 1 to 5 is used to record condition (status) and the criteria became fields inscribed in the ACCESS system. The scale, along with the other fields, was agreed beforehand on the grounds that it was a 'good' method. ‘Good’ here, consistent with Garfinkel’s findings (reference needed), meant simply that members arrived at agreements with a degree of consistency. A text box in the system also allowed the group to record biography, special details, whether the wagon is rare or typical, is worth buying or not etc. The data, both in the ring binder and in the system, was then available for interrogation, and thus to interpretation. Thus the curator was able to show us an example and say, 'this wagon is a fine example of a particular type of clay wagon ... it was used in 1947, and played a particularly important part in the development of the paper finishing trade.' One feature of this ongoing work was that it implicated two distinct kinds of classification work. The first is taxonomic work, which involves laying down the terms by which artefacts can be organised in the first place, and thus into which, with revision, all relevant objects can be placed. The second, however, lies in the special qualities of individual items. That is, the group orients its recording of information not only to the taxonomy, but also to each object’s ‘special’ qualities, or ‘uniqueness’.

For the most part, this system of coding and incorporating information into a small database worked well. Problems arose, however, as the network of people involved began to expand and we were able to observe first hand some of the consequences when being shown the system. Here, the reliability of members’ terms came into question, as the terminology used when new ‘spots’ were input into the database became increasingly variable. Particular confusions arose over the status of one variety of motorised wagon, termed a ‘Mogo’. It seems there are a number of different kinds of Mogo, identified by weight, for instance the 8 and 12 ton versions. As the curator showed us how he used the system, he said,

"I’ll bring up Mogo, cos I know there are two of them. I can use search criteria like these ... oh, there are five. Hang on, I’ll try again. There you are, those two ... I can’t see why I got five the first time. It’s to do with the order you search in, but I didn’t know there were five of them."

12 ton British Rail mogo van with brown sides

Of course, problems of search ordering are well known, but that is not the point here. What had happened was that different people had made assumptions about the appropriate terminology and reached different conclusions. Thus, ‘spots’ had been entered variously as ‘12 ton Mogo’ or ‘Mogo 12 ton’. Some entries of ‘Mogo’ had been capitalised, others entered in lower case. Members had taken for granted their knowledge of Mogos and assumed that the database was configured in that respect, whereas it had been configured according to the senior curator’s categories alone. There followed a lengthy and animated discussion which we will call a ‘what’s in a name?’ discussion and which we need not detail. Arguing about a name, however, was indicative of the need to identify fields in such a way that they both incorporate and exclude in ways that are in common with members' categories. This lays out a potential problem for the enlargement of use, in that standardisation, however desirable, may require us to be sensitive to the changing user population, and variations in the common-sense categories they deploy. General conclusions we might reach from this example include:

Conclusion.

‘Evaluative’ ethnographies (Hughes et al, 1994) have in the main been used to demonstrate specific ways in which technologies have failed to ‘fit with’ work practice, and on occasion to reveal how ‘work arounds’ can obscure problems with the technology. More generally, it has been suggested that their task is to deal with ‘uncertainty’ (see Twidale et al, 1994; Randall et al, 1995) Our task is not to be overly critical about existing systems, for in Europe at least the history of database applications for museum work is a history for the most part of adapting existing software to support some fairly standard functions. Indeed, large parts of museum work currently involve no use of computer technology at all. That it should be so, as we have suggested, is arguably because the naivety of museum staff has made the elicitation of ‘requirements’ a difficult task, and therefore the prospective success of computer systems in museum work deeply uncertain. Our purposes here lie in the evaluation of database technologies in a rather different sense. We are not concerned with the ‘failure’ of particular systems, for our impression is that systems in use are hardly of the most advanced kind. The evaluation, if that is what it in fact is, concerns a set of organizational and work- related issues which provide some initial scope for understanding the notion of a ‘sense of order’, and how deconstructing the term might help us reduce the level of uncertainty contained in database use. That sense of order, we suggest, is arrived at in a series of contingent ways which are reliant on work done co-operatively, sometimes in small and fairly coherent groups, sometimes across the boundaries of responsibility, and sometimes by virtue of the way in which general assumptions about purpose are organized.

In a climate where museums are under an ever increasing commercial pressure, and where once secure roles are becoming challenged, the task is more to do with applying our study of work practices to the general problem of ordering and classifying the myriad objects which museums keep in their collections, objects which can include artefacts, texts, images, whole archives, and so on. What we do want to do is suggest some of the subtlety of classification work in such a way that the next generation of systems might support work as it is practically accomplished, work that for the most part has remained ‘seen but unnoticed’, in Garfinkel’s terms (1984) to the procurers of existing systems. Of course, Garfinkel raised the issue of classifying in terms of ‘common sense choices’ in his analysis of the documentary method (ibid), and we want to see classification in the museum context in much the same way. Classification, when considered as a job of work, can be seen as orienting to, and contingent upon, a number of factors which have to do with the way objects and texts come to attention, by whom, what the local relevancies of the museum are, the research interests of curators, and the prospect and desirability of display. All of these factors may impact on what classification is deemed appropriate, and lead to the conclusion that artefacts may in principle be classified in any number of ways. Indeed, as we have seen, they frequently are. The contingent status of artefacts, the invisibility of rationale, the 'work done', have direct corollaries in design terms. We have suggested a range of issues that seem germane to the general problem, including the consideration of objects and collections as ‘careers’ and thus change, how classifications emanate from 'seeing' artefacts in terms of their value in the collection, how they are impacted upon by a series of local relevances, how it is dependent on the practiced reading of acquisitions, relate to narrative possibilities, depend on the ‘job in hand’, and on the ‘authority’ of the user.

The comprehensive electronic organisation of data about museum artefacts would be greatly enhanced by the prospect of parallel classification schema, search pathways, and sophisticated database interrogation techniques which would allow the contingent uses we have outlined above. Those with a more cynical view of sociological input into system design will not be surprised to hear that we proffer no solutions. The point here is to raise initial questions concerning how working with database systems might allow, rather than obstruct, contingent classification. The task here, as we construed it, was simply to do the ethnographic work, evaluate the work of museum staff both in their use of technology and without it, and understand how in practice they ‘managed’ their collections.

In this paper, we have sought to raise some initial issues concerning the use to which potential electronic resources for collection management may be put, based on the observations we have undertaken. We hope, as the work unfolds, to begin to specify how they may be dealt with through a more detailed and thorough description of classification procedures, visitor behaviour, and educational work. We have not raised at all the problem of relating professional use to visitor needs, and believe that if any of these possible benefits are to be realised, a substantially more nuanced view of the work of museum staff and visitors is needed. After all, the objects and their inscriptions are not merely examples of the past but are instructions as to 'how to tell about the past'. In a sense, a special, respected, experienced, entrusted authority, resides in the museum, whereby a tacit contract exists between the museum and the audience. The issue of providing appropriate 'pathways' through complex and changing information resources, we suggest, is central to this . If such technology were to incorporate visitor uses as well, then the relationship between professional contingencies and the degree to which they match or otherwise the assumptions and practices of visitors will required.

Bibliography.

Baudrillard, J., 1983, Simulations, New York, Semiotext(e)

Bennett, T., 1995, The Birth of the Museum, London, Routledge

Berger, P. and Luckmann, 19--, The Social Construction of Reality,

Burgin, V., 1986a, Between, Oxford, Blackwell in association with the ICA.

Burgin, V., 1986b, The End of Art Theory: Criticism and Postmodernity, Basingstoke, Macmillan.

Donato, E., 1979, The museum's furnace: notes towards a contextual reading of Bouvard and Pechuchetí, in J. Harrari (ed.) Textual Strategies: Perspectives in Post- Structuralist Criticism, Ithaca and London, Cornell University press.

Ellis, M., 1991, The Micro Gallery: A Multimedia Resource for the Gallery Visitor', in Hypermedia and Interactivity in Museums: Proceedings of an International Conference, D. Bearman (ed.), Pittsburgh: Archives and Museum Informatics, 321

Foucault, M., 1980, Power/knowledge: Selected Interviews and other writings, Brighton, Harvester Press

Garfinkel, H., 1984, Studies in Ethnomethodology, Cambridge, Polity Press

Heath, C. and Luff, P., 1996, Documents and Professional Practice: "bad" Organizational Reasons for "Good" Clinical Records, in Proceedings of CSCW ‘96, Boston, Mass., ACM Press

Hughes, J., Randall, D. and Shapiro, D., 1991, From Ethnographic Record to System Design: Some Experiences from the field, CSCW, An International Journal, Vol 1

Hughes, J., King, V., Rodden, T. and Andersen, H. , 1994, Moving Out of the Control Room, Proceedings of CSCW ‘94, ACM Press

Jirotka, M. and Goguen, J., 1994, Requirements Engineering: Social and Technical Issues, London, Academic Press.

Lakota, R.A., 1975, The National Museum of Natural History as a Behavioural Environment, Final Report, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Office of Museum Programs

Landow, G.P. (ed.), 1994, Hyper/text/Theory, London, The Johns Hopkins University Press

Lyotard, J-F, 1984, The Postmodern Condition: A Reort on Knowledge, Manchester University Press

Kopytoff, I, 1986, The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditisation as Process, in A. Appadurai (ed.), TheSocial Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Macdonald, S. and Fyfe, G. (eds.), 1996, Theorising Museums, Oxford, Blackwell/ The Sociological Review

McManus, P.M., 1991, Food for Thought: An Evaluation Study, The Science Museum Interpretation Unit

Porter, G., ‘Seeing through Solidity: A feminist perspective on museums’, in S. Macdonald and G. Fyfe (eds.), Theorising Museums, Oxford, Blackwell/The Sociological Review

Pycock, J. and Bowers, J., 1996, Getting Others to Get it Right: An Ethnography of Design Work in the Fashion Industry, in Proceedings of CSCW ‘96, Boston, Mass., ACM Press

Randall, D., Rouncefield, M. and Hughes, J., Chalk and Cheese: BPR and Ethnomethodologically Informed Ethnography in CSCW, in H. Marmolin, Y. Sundblad and K. Schmidt, Proceedings of the fourth European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Stockholm, Sweden, Kluwer

Randall, D. and Hughes, J. A., 1994, Sociology, CSCW and Working with Customers, in P. Thomas (ed) Social and Interaction Dimensions of System Design., Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Star, S. Leigh and Griesemer, J.R., 1989, Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39, Social Studies of Science, Vol 19, pp 387-420

Twidale, M., Randall, D. and Bentley, R., 1994, 'Situated Evaluation for Cooperative Systems', Transcending Boundaries: Proceedings of CSCW '94, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, ACM Press.